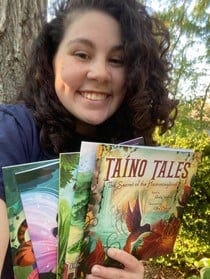

Why I Can’t Represent Myself (Even Though I’m a Literary Agent)

Welcome to My Literary Life—where I share the messy, magical mix of teaching, parenting, writing, and agenting. Free subscribers get occasional posts, while paid members unlock the full archive, behind-the-scenes peeks, and creative resources from my own vault. If you’re a reader, teacher, or writer craving a little spark, you’ll feel right at home.

Recently, in the comments section of my Substack, I noticed a theme:

“You’re a literary agent and an author. So…can’t you just represent yourself?”

It wasn’t the first time I’d been asked. In fact, the question comes up more often than you might think—at conferences, in DMs, during casual conversations with other parents at my kids’ school. But every time, my answer is the same:

No. Absolutely not.

Even if I could represent myself (which I can’t), I wouldn’t. Because doing so would not only be a disservice to me, but also to the authors I represent. And in publishing—an industry built almost entirely on trust, relationships, and reputation—that’s a line I can’t afford to blur.

So today, I want to peel back the curtain and share why agents never represent themselves, and why I wouldn’t want to even if I had the option.

The Paradox of Being an Agent-Author

On paper, it sounds logical: I already negotiate contracts. I already pitch editors. I already know how to position a book in a query letter. So why not just skip the middleman (or, in this case, myself as the middleman) and go straight to the editors I know?

Because the reality is this: what works in my favor as an agent would backfire on me as an author.

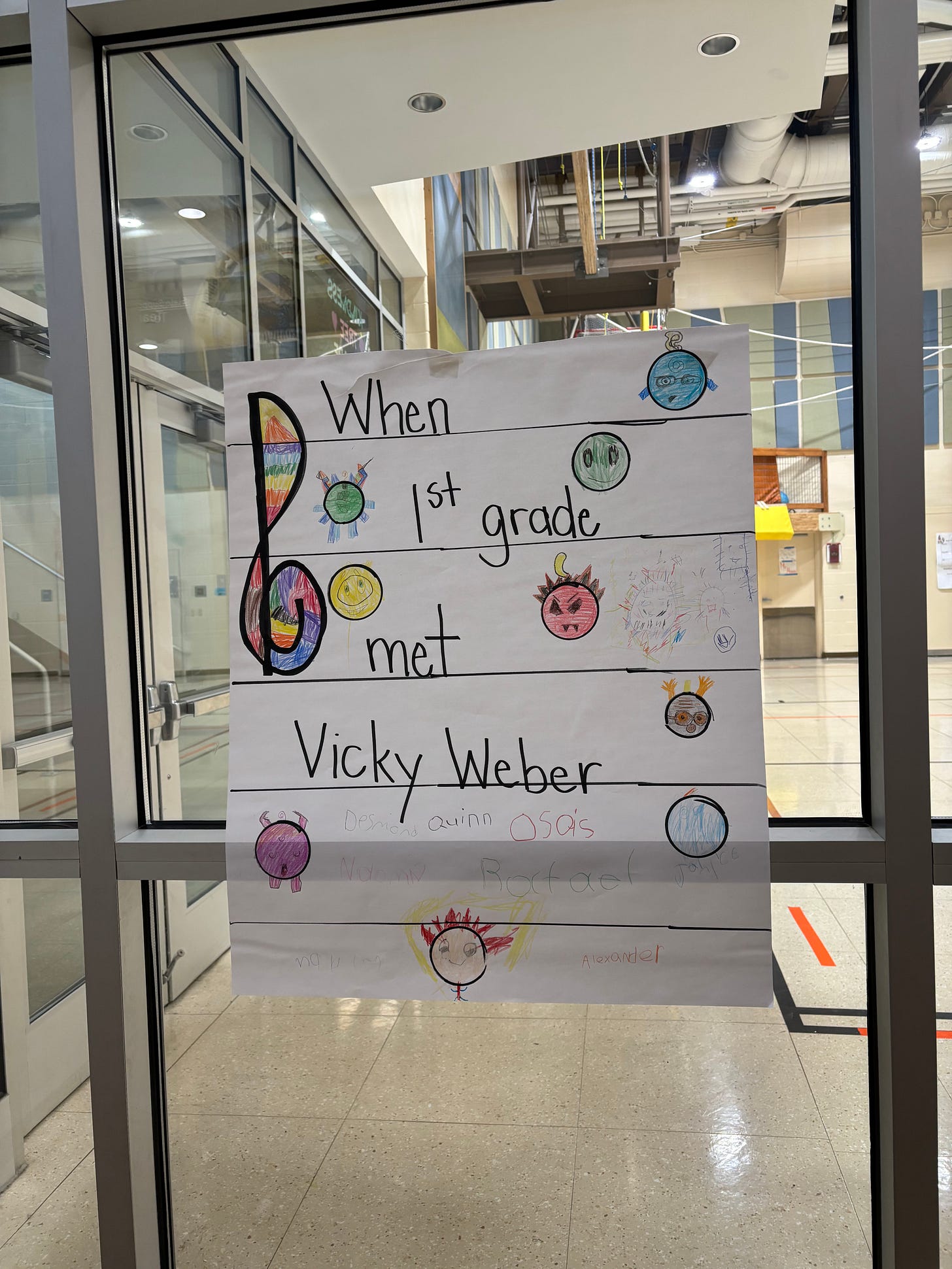

Publishing is person-to-person, people-to-people. If an editor sees me pop up in their inbox with my own manuscript, it shifts something in the relationship. Instead of “Vicky the agent who advocates for her authors,” I become “Vicky the agent trying to get a leg up.” And that shift doesn’t just impact how they see me—it has the potential to ripple out onto the authors who’ve trusted me with their careers.

I never want an editor to open an email from me and feel that little twinge of “ick.” Because once that door cracks open, it’s all too easy for them to associate that same feeling with my clients. And that is the opposite of advocacy.

Why Objectivity Matters (and Why I Don’t Have It With My Own Work)

Another piece of this puzzle: objectivity.

I tell my authors all the time: you can and should self-edit, but you should never be the final editor on your own book. Why? Because you’re too close to it. You know the characters, the intention behind every scene, the joke that was funny in your head but maybe doesn’t land on the page.

And when you’re that close, you miss things.

Agenting is no different. My job is to see the market clearly, to weigh comps and positioning, to anticipate how an editor will read a manuscript and where it fits on their list. But when it’s my manuscript? I can’t read it with that same distance. I can’t un-know the struggle that went into drafting it or the hopes I’ve pinned to it.

It’s the same reason doctors don’t perform surgery on themselves, or why therapists have therapists. We all need someone outside of ourselves to hold up the mirror.

The Buffer Zone: Why Agents Are “The Bad Guy” (and Why That’s Good)

Here’s another benefit of having an agent: they get to be the bad guy.

When I’m negotiating on behalf of a client, I’m the one asking the hard questions about money. I’m the one pushing back on contract clauses. I’m the one saying, “Actually, no, we can’t accept that.”

And that’s exactly how it should be.

Because it means the author can maintain a warm, positive, collaborative relationship with their editor. They get to stay in the creative lane while I handle the messy business lane.

If I tried to represent myself, I’d be blurring those roles. Suddenly, I’d be the one asking my editor for more money and the one who has to turn around and brainstorm edits with them the next day. And that…doesn’t exactly set the stage for a healthy working relationship.

A Matter of Ethics and Perception

Then there’s the optics.

Picture this: you’re an editor, and an email pops up from a literary agent you know. But instead of pitching a client, the subject line says: “Submission: My Book.”

Awkward, right?

Even if that agent is brilliant and hardworking, it doesn’t look good. It raises questions. Was this person only interested in becoming an agent so they could sell their own work? Is this fair to the thousands of authors querying the traditional way?

And let’s be honest: publishing isn’t always fair. There are referrals. There’s luck. Sometimes people get priority treatment over others. That’s the reality of the business.

But here’s the important distinction: even with those inequities, the guardrails still matter. Authors query agents. Agents query editors. Editors don’t acquire their own books. And yes—even agents and editors who are also writers still have to query just like everyone else.

The system isn’t perfect, but those lines keep it from slipping into something much worse: a free-for-all where conflict of interest and self-dealing become the norm.

So What Does It Actually Look Like Behind the Scenes?

Here’s where things get even trickier—and where I think a lot of people are most curious.

Because it’s one thing to say, “I can’t represent myself.” It’s another to explain how those lines get drawn in practice, especially when you’re both an agent and a writer, or an editor and a writer.

And this is the part that I think will surprise you most.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to My Literary Life to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.